Illustration by Davor Pavelic/Ikon Images

Health

Happy? Want to learn how to be?

Harvard professor aims to ignite mass movement through podcasts, books, new lab at Kennedy School for research, leadership training

Arthur C. Brooks launched a course four years ago to teach his students not only how to increase their happiness, but how to make those around them happier as well. Now, he’s looking to spread the word to everyone, everywhere.

“I’m trying to make a happiness movement in the public,” said Brooks, the William Henry Bloomberg Professor of the Practice of Public Leadership at Harvard Kennedy School and professor of management practice at Harvard Business School.

Besides his popular Business School course, Brooks has spread his ideas through his podcast (“The Art of Happiness with Arthur Brooks”) and books (“From Strength to Strength,” “Love Your Enemies”) and, for the last two years, a weekly Atlantic column. Earlier this year he and his team launched the Leadership & Happiness Laboratory, which looks to investigate what science tells us about achieving happiness and how to spread it. The first cohort of students and a group of scholars began work with the lab this month.

“I want grass tops and grassroots,” said Brooks. “My books, and my podcast, and my Atlantic columns, that’s grassroots. Grass tops is Harvard — that’s my students that I teach in the lab [and it’s] leading the leaders so that they see themselves as happiness teachers, whether they’re formally teachers or not.”

So what is his secret recipe for happiness?

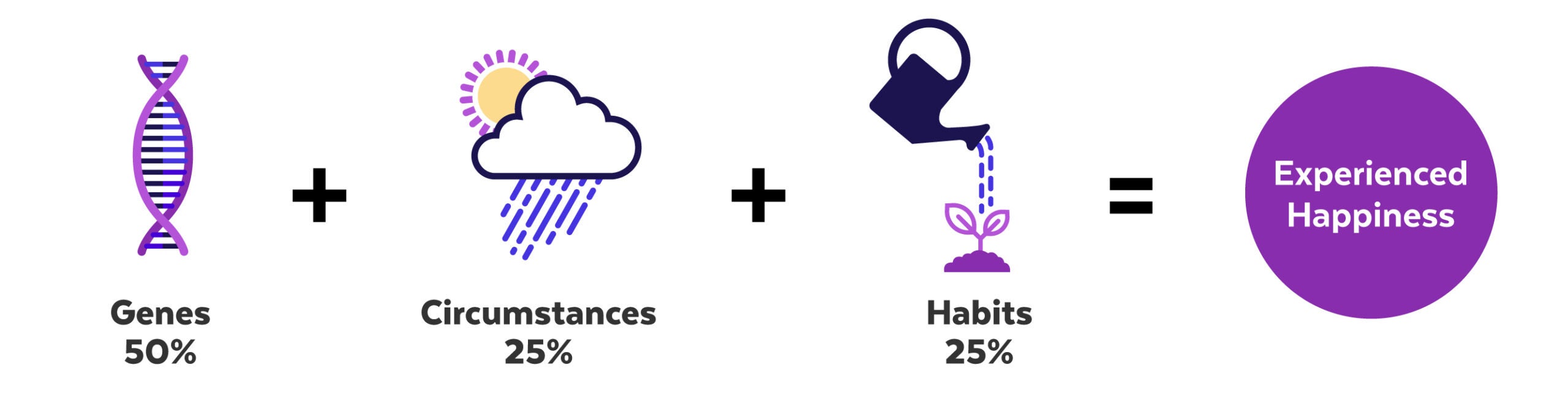

It’s complicated, Brooks says, but the basis of your happiness can be split into three parts.

“Half of your happiness is genetic, and a quarter is circumstantial — more or less,” he said. “But your habits are king because your habits give you 25 percent [of your happiness] directly. They can also change your circumstances. And they can actually help you manage your genetics.”

Arthur Brooks’ happiness formula.

Graphic by Judy Blomquist/Harvard Staff; source: Arthur Brooks

That equation is how he began his first column in the Atlantic, “How to build a better life,” and it’s just one idea he teaches his students. Brooks’ seven-week course takes a deeper dive into the philosophy, neuroscience, and social science of human happiness, including research on emotions, relationships, reward systems, and the value of embracing a transcendent purpose in life.

Brooks, a self-described data-driven scholar at heart, takes on topics such as “Affect and the Limbic System,” “The Neurobiology of Body Language,” “Homeostasis and the Persistence of Subjective Well-Being,” and “Oxytocin and Love.” And he blends those ideas with time-tested wisdom on what he calls the “building blocks of happiness”: family, career, friendships, faith.

“A lot of people think it’s a very subjective experience, because they think about happiness as feelings, but happiness isn’t feelings. Feelings are evidence of happiness,” he said.

He added that his students also look at the work through a lens of leadership, and how happiness principles can be applied in their lives with coworkers, kids, church members, or any others who look to them in a leadership role. That’s one of the reasons he’s passionate about bringing the work to leaders outside the Harvard community, one of the goals of his new lab.

“There are lots of happiness labs that are coming up with the basic science, which is super important, and we’re going to be paying attention to that. But there’s not that many places that say, ‘How do you spread these ideas?’” he told the Gazette.

Better leaders, Brooks says, make for better, and happier, organizations and societies.

“When you lead with happiness, when you’re a happiness professor in business, or government or nonprofit, then you’re just a way better leader,” he said.

A social scientist by training, Brooks has been studying happiness off and on since the 1990s. Throughout his 20s he juggled college and ambitions of becoming a professional French horn player. During grad school, where he studied economics, he found a love of behavioral analysis. And at 31, Brooks left music and earned an M.Phil. and Ph.D. in public policy analysis from the Rand Graduate School in Santa Monica, California.

He’s taught at Syracuse, and for 10 years, served as the president of the conservative American Enterprise Institute think tank before deciding to dedicate himself to the topic.

Since coming to Harvard in 2019, Brooks has discovered that he is not the only one who wants more happiness in life. Both sections of his course have become so popular that they fill up months in advance.

“Since I’ve been doing this full-time, my happiness is up 60 percent,” he said.

Brooks aims to ensure the lab hits the ground running. In the works is a happiness and leadership co-curricular for a select group of Kennedy School students who will be conducting preliminary research from February to April. The lab is also organizing a trip to India in March to meet the Dalai Lama — a relationship Brooks has fostered through his years of happiness work. Also queued up is a conference hosted by the HKS Center for Public Leadership and the happiness lab in June.

For members of the wider public the lab is partnering with HarvardX to create a free online course, “Managing Happiness,” that will run for six weeks starting in March. The class is intended to introduce participants to the basic science of happiness and psychological strategies to turn lessons into lasting habits.

Brooks says he has high hopes for turning his personal preoccupation into a real movement.

“I want to see more and more and more people doing happiness classes, people who touch this laboratory, who are exposed to the information, I want to see them actually out there teaching happiness stuff, at all different levels,” he said.